Hunters don’t need a team of researchers to tell us that making noise in the woods scares the game – we’ve known that for millennia. What we can’t always say is how a lot of which wild critters endure before they run away, or which common outdoor activities put them under the most stress. Now some of these questions have been answered thanks to a new study that examined how noise from increasing outdoor recreation affects nature.

The studywhich was published in the July 2024 issue Current biology, examined how games respond when confronted with the vocal and non-vocal sounds of small and large groups of hikers, trail runners, mountain bikers, and all-terrain vehicle users. All told, animals in the wild were 4.7 times as likely to flee from all human sounds, and those critters stayed alert three times longer than when no sound was played. Additionally, wildlife abundance at the camera locations was one and a half times lower the week after recreational sound was played.

To conduct the study, researchers from the US Forest Service and several Western universities deployed camera traps and speakers in the Bridger-Teton National Forest in Wyoming. When activated, the speakers played pre-recorded sounds of outdoor users, plus control sounds of non-human activity and no sound at all. They collected and analyzed data from 1,023 audio trigger events during 4,444 trap nights from mule deer, elk, red fox, black bear, elk, pronghorn, cougar, coyote and wolves.

Illustration by Shea Coons / Current Biology

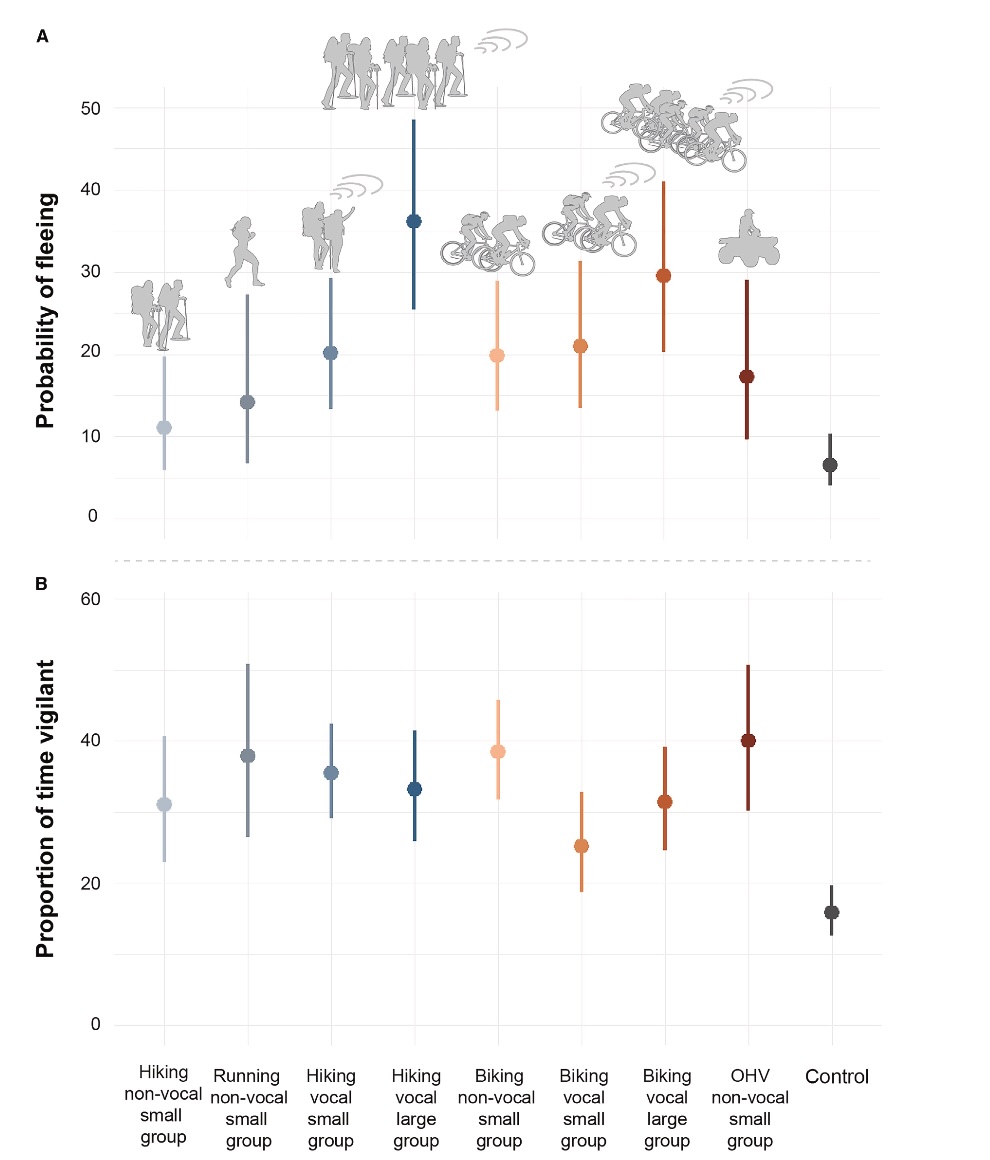

The shots that scared animals the most were large groups of walkers; animals were eight times more likely to run away when they heard talkative backpackers and responded similarly to large groups of vocal cyclists. Although wildlife did not flee as often from the sounds of all-terrain vehicles, animals remained alert the longest after hearing four-wheelers nearby, compared to any other user group.

Nearly all of the animals in the study were stressed by human recreational noise, including combinations of large and small groups of vocal and non-vocal hikers, cyclists, trail runners, and non-vocal OHV users.

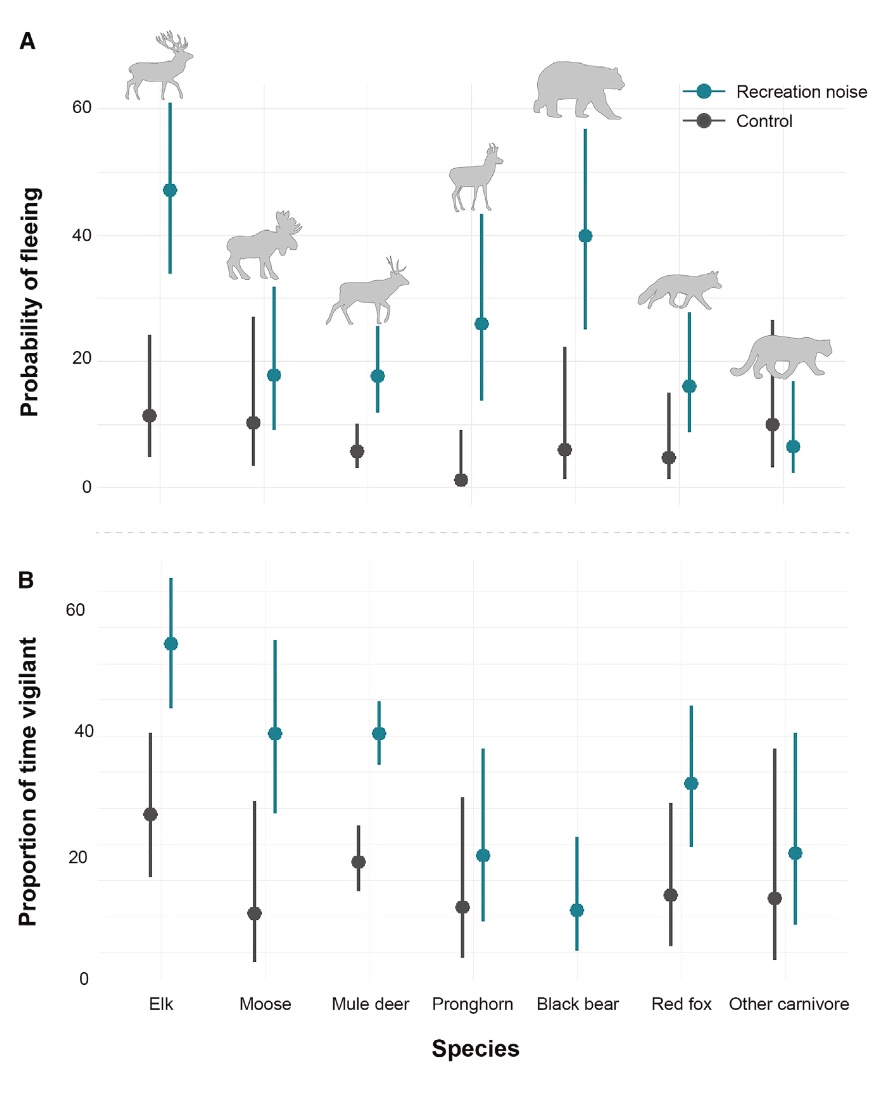

Of the animals studied, moose were the most sensitive to human noise and had a nearly 50 percent chance of fleeing; they also remained alert the longest after running away. Black bears were the second most likely escapee with a probability of about 40 percent, followed by pronghorn (25 percent). Elk, mule deer and coyotes all recorded about the same.

“Although elk and mule deer were less likely to flee than elk, black bears and pronghorns, both have been shown in other studies to avoid areas with human recreation,” the researchers wrote. “However, moose have also been shown to select for areas with human presence, presumably as a human shield effect against predators, suggesting a risk-reward trade-off and that responses to recreational noise may be situation-dependent.”

Large carnivores appeared to be the least sensitive to human noise; Cougars responded no differently to recordings of human recreation than to no sound at all. However, researchers noted that there were limitations to the conclusion that human recreational noise does not bother the big cats.

“Although carnivores in our study had a weak behavioral response to recreational noise, they may still have experienced physiological effects that we could not observe. For example, higher levels of stress hormones have been found in wolves in response to snowmobile recreation, and although few behavioral changes were observed, acute increases in heart rate have been documented in black bears in response to unmanned aerial vehicles. Therefore, the absence of an obvious behavioral response may not equate to a lack of response, and our results likely underrepresent the magnitude of recreational noise effects.”

Naturally, the study did not look at factors such as human odor or the visual presence of recreation, but that was not the intention; researchers wanted to specifically address how noise affects nature. The result, they say, is that even low levels of recreational noise can cause wildlife to avoid primary habitat – and the food and cover it provides. All these findings could ultimately lead to different (read: stricter) recreation rules.

In a grizzly country where people are being advised to travel in larger groups and make a lot of noise, researchers say recreation managers could consider changing the rules to “restrict recreationists to stay on designated trails.”

Read next: Officials in Alaska are killing 81 bears and 14 wolves to help caribou calves

The full study is not currently available for free and the lead author, Katherine Zeller, was not immediately available for comment. While the details of the study are interesting, the lessons for hunters who want to be successful are familiar: hunt alone or in small groups, get away from other people, and keep your mouth shut. Oh, and riding your ATV to your deer camp isn’t as inconspicuous as you might think.

syndication@recurrent.io (Natalie Krebs)

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.