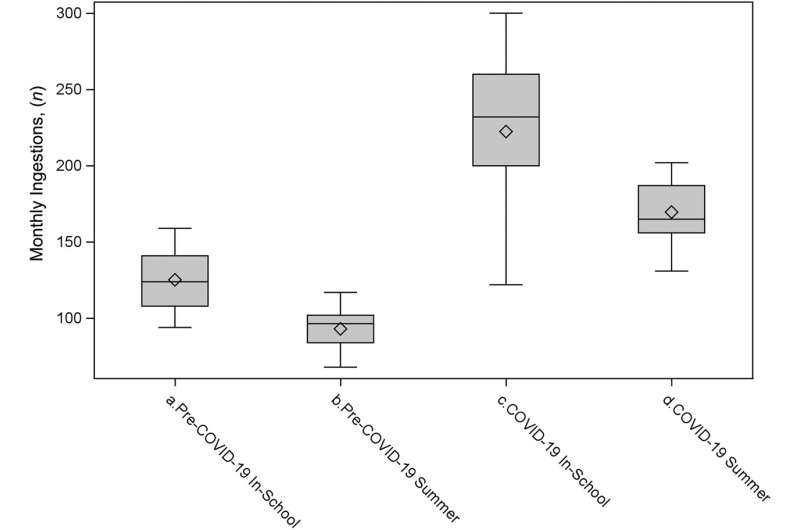

Distribution of monthly admissions for paracetamol intake by era, comparing school months with summer months. Credit: Hospital pediatrics (2024). DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2023-007424

Even as classrooms, offices, concerts, and weddings begin to look more like their pre-2020 counterparts, the traces of the global pandemic remain visible in new norms and long-term issues.

“COVID-19 has affected an entire generation of individuals at every level,” said Khalid Afzal, MD, a child psychiatrist at the University of Chicago Medicine.

In conversations on social media and other forums, many people share the common sentiment that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on mental health – that it represents a collective trauma from which we will take years to heal. Now that researchers have a few years of data to analyze, they’re starting to more fully unravel that mental impact from an empirical perspective.

The toll of the unrest

According to Afzal, suicide attempts and suicide-related emergency room visits for both children and adults increased significantly within a few months of the pandemic’s onset, as did the number of completed suicides. Data from the CDC and researchers across the country also show a jump in the rates of conditions like anxiety and depression, and psychiatric treatment centers have reported longer wait times as demand exceeds capacity.

“After a few months, it dawned on people that the situation was not going to change anytime soon,” Afzal said. “And the more they became isolated, the more that isolation compounded with other stressors like financial worries and fear of dying. It’s quite disheartening to see the toll it took on people.”

He said the interruption of major life milestones such as graduation ceremonies was especially traumatizing for children and adolescents, as was the lack of privacy and relational tensions caused by families confined to small spaces.

How a respiratory virus can affect the brain

It makes sense that the massive social disruptions of the pandemic have caused spiritual distress. Less obvious – but still important – are the direct consequences of biological changes due to COVID-19 that affect the brain and behavior.

Although COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory virus, it attacks many systems in the body and can cause dangerous inflammation. Health experts quickly realized that adults with particularly severe psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 infection; their cases were more likely to be medically serious, and many experienced a worsening of their psychiatric disorders. “It wasn’t necessarily an intuitive outcome, but the trend became apparent very early on,” says Royce Lee, MD, a psychiatrist and researcher at UChicago Medicine.

People who did not have a psychiatric diagnosis before contracting COVID-19 were also not invulnerable to neurological effects. Many experienced “long COVID” symptoms such as pain, mental cloudiness, lack of sustained attention, memory problems, depression, anxiety, fatigue and irritability.

“There are causal pathways in both directions between immune activation and brain function, which influence behavior and emotions,” says Lee, whose research often focuses on those pathways. “In particular, there is a very strong link between immune activation and anger regulation.” Immune activation can come directly from the virus itself or be caused indirectly by stress and anxiety.

Lee pointed out that even people who don’t notice brain fog or have observable “long COVID” disorder can still experience more subtle symptoms, such as increased irritability. emotions.

“When abrupt shifts in mental health occur, it is still relevant to ask yourself, ‘When was my last COVID-19 infection? And how does its timing correspond to my change in mental status?’” Lee said.

Staying proactive about mental health and safety

Increased rates of suicide and psychiatric disorders have made mental health safety a particularly high priority in the wake of COVID-19. A group of UChicago researchers recently published a study highlighting safety concerns associated with a substance found in countless homes: acetaminophen.

“It’s important to think about how something so easily accessible could be used for something very dangerous,” said first author Wendy Luo, a third-year student at the UChicago Pritzker School of Medicine. “As the pandemic has spread and children have begun to struggle even more with mental health, it makes sense that they have often turned to what is available at home.”

Even before 2020, researchers had noted an increase in calls to poison control hotlines related to suspected suicide attempts by acetaminophen overdose. Experts also documented higher suicide rates among students during the academic year compared to the summer months. Luo and her collaborators wanted to investigate whether COVID-19 further exacerbated these trends.

They compared acetaminophen-related hospitalizations from the pre-COVID-19 era (January 2016 – February 2020) with the COVID-19 era (March 2020 – December 2022). They found that intentional acetaminophen ingestion was much more common among children ages 8 to 18 during the COVID-19 era, and that rates remained highest during the school year, even though many schools were at least partially remote during that period .

“We hope these results send a message that we need more resources in schools, as we consistently see the highest rates of self-harm during the months students spend in school,” Luo said. “And when major school disruptions occur during the pandemic, such as the shift from in-person to virtual and hybrid, some children struggle even more with the uncertainty and isolation.”

We move forward while COVID-19 lingers

“As a society, we need to educate ourselves, recognize that these mental effects are very real, and provide individualized support and accommodations for people as they recover,” Afzal said. “It’s important to see people as survivors rather than victims. I think people are naturally resilient, but the way we talk about things affects the way we move forward.”

Like Luo, Afzal pointed to the need for more resources in multiple contexts. He said some hopeful trends have already emerged, such as an increase in the number of medical students specializing in psychiatry, but added that there is plenty of room for different decision-makers to increase the capacity of mental health services and provide a broader offer a range of services. solutions and support.

Lee likes to point to the Spanish flu as a good teaching tool for understanding some of the effects of a global pandemic. Fortunately, the past may offer some hope:

“There was a kind of delayed response: in the two or three years after that virus outbreak, psychiatric disorders increased in prevalence and some new ones emerged, probably due to immune activation,” he said. “It was almost like a neuropsychiatric second wave of the pandemic. But then it became quiet again and it became more or less normal. I think it is possible that we will see similar trends in this pandemic.”

“COVID-19 and intentional toxic ingestion of acetaminophen in children: a research letter“was published in Hospital pediatrics in April 2024. Authors included Wendy Luo, Isabella Zaniletti, Sana J. Said, and Jason M. Kane.

More information:

Wendy Luo et al, COVID-19 and intentional toxic ingestion of acetaminophen in children: a research letter, Hospital pediatrics (2024). DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2023-007424

Quote: Social and Biological Factors Both Contribute to Mental Health Issues in the Wake of COVID-19 (2024, June 3), retrieved June 3, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-06-societal-biological-factors -contribute -mental.html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.