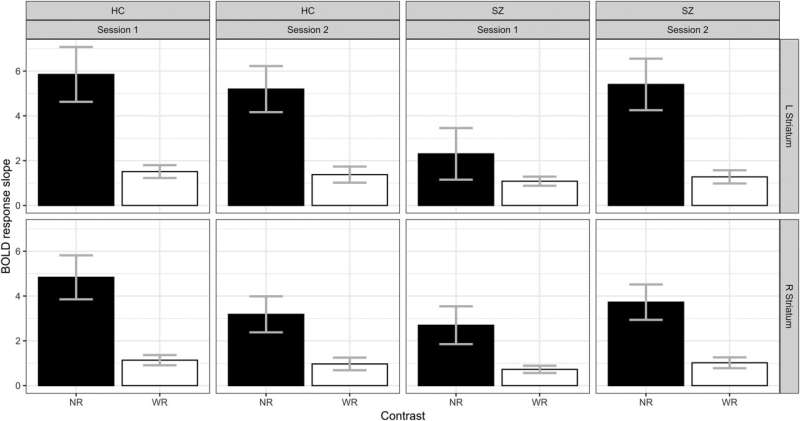

Comparison of sessions 1 and 2. Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response slopes in the narrow (NR) and broad (WR) reward ranges separately, in the left and right striatum. Credit: Brain (2024). DOI: 10.1093/brain/awae112

Schizophrenia, which affects up to 1% of the population, is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by multiple symptoms. One of the most common, and for which there is no treatment, is apathy and lack of motivation.

By comparing neural activation between a group of patients and a control group during a reward game, a team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), in collaboration with researchers from Charité Berlin, has unraveled the neural basis of this disorder.

The brains of people with schizophrenia are unable to subtly distinguish between different levels of reward, hampering their motivation to perform everyday tasks.

Published in the magazine Brainthis findings suggest several possible treatments, including brain stimulation and targeted psychotherapy.

When we think of schizophrenia, we first think of hallucinatory or delusional ideas, such as ideas of persecution. Less visible, however, are apathy and lack of motivation, which are just as burdensome in daily life.

“Lack of motivation is at the root of the problems that people with schizophrenia experience in pursuing their studies, keeping a job or maintaining social contacts,” explains Stefan Kaiser, professor at the Department of Psychiatry and the Synapsy Center for Neuroscience and Mental Health Research of the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine and head of the Department of Psychiatry at HUG, who led this research.

“In addition, the antipsychotics prescribed for hallucinations and delusions have no effect on motivation, for which there is currently no effective treatment.”

What’s happening in the brain, specifically the neural reward system, the seat of motivation and behavioral responses? Using MRI, scientists wanted to determine whether people with schizophrenia show different neural responses compared to people without a mental disorder, and whether these responses correlate with clinical observations.

Activating neural responses through a game

The scientists enrolled 152 volunteers — 86 people with schizophrenia and 66 “controls” of similar age and gender — to play a reward game in an MRI scanner to observe the activation of their brain regions. The experiment took place in three phases: an assessment of motivation in different contexts, an initial game session and, three months later, a second session identical to the first to measure the stability of the cerebral response over time.

“To stimulate the reward networks, the game allows you to win money, up to CHF 40. At the beginning of each session, a circle appears indicating the possible reward: an empty circle (winnings 0), a circle with a bar (winnings between CHF 0 and 0.4) or a circle with 2 bars (winnings between CHF 0 and 2)”, explains Mariia Kaliuzhna, a researcher at the Department of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE and first author of this study.

“Then three more circles appear. The one on the right or the one on the left is different from the other two; players have to press the corresponding button as quickly as possible. Finally, a red bar indicates how high the reward was, at which point the neural network is activated. The tests continued like this for about fifteen minutes.”

Hypoactivation or satiety

During the first session, individuals with schizophrenia showed lower activation levels compared to the “controls”, especially when the reward was low, as if their brains were struggling to activate. On the other hand, during the second session, many of them saw their brain activity increase significantly, even more than the control group who maintained the same level of activation.

“Despite appearances, these results are not contradictory. In fact, they indicate that in people with schizophrenia, the neuronal response cannot adapt to the reward context. There is hypoactivation or satiety, which suggests a failure to regulate this brain structure.

“In both cases, the person cannot correctly evaluate the reward to adjust his behavior. The result is an inability to respond to small everyday satisfactions, such as a meal with friends or a pleasant walk, typical of apathetic behavior,” Kaliuzhna explains.

These results open up a number of therapeutic avenues that would target precisely this neuronal activation defect. “For example, psychotherapy that focuses on the perception of reward and pleasure to strengthen the motivation to engage in social behavior, or the use of non-invasive brain stimulation, a technique that is already used to treat depression,” Kaliuzhna explains.

“However, these techniques are complex and need to be validated in clinical trials before they can be applied in the clinic.”

More information:

Mariia Kaliuzhna et al, Adaptive reward coding in schizophrenia, its change over time and its relationship with apathy, Brain (2024). DOI: 10.1093/brain/awae112

Quote: Why Schizophrenia and Apathy Go Hand in Hand (2024, July 2) Retrieved July 3, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-07-schizophrenia-apathy.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair dealing for private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The contents are supplied for information purposes only.

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.

Healthy Famz Healthy Family News essential tips for a healthy family. Explore practical advice to keep your family happy and healthy.